Landing that position, followed by the election of a Republican president two years later, brought Murkowski closer to winning a divisive, decades-long battle that pitted Alaska's politicians -- including her own father -- against environmentalists.

For Murkowski, this isn't just a political accomplishment, it's a personal one. Her father, former Gov. and Sen. Frank Murkowski, also was energy chairman two decades ago and attempted to usher through the same legislation, alongside other Republican giants in Alaska's small delegation: Rep. Don Young and the late Sen. Ted Stevens.

The previous bill cleared both chambers of Congress in 1995, but it was vetoed by then-President Bill Clinton. In an interview with CNN, Murkowski recalled the event with heartbreak. "That was crushing."

Ten years later, this time with Lisa Murkowski in office in the place of her father, the Alaska delegation once again came close to opening up ANWR in December 2005, but was unable to get it past Democrats and some moderate GOP lawmakers.

And those were just the major moments of a debate that dated back to the late 1970s in Congress. Young, Alaska's at-large representative and the longest serving member of the House, told Murkowski that when he voted on the tax reform bill in the House this week, it was his 13th time passing a bill to open up ANWR.

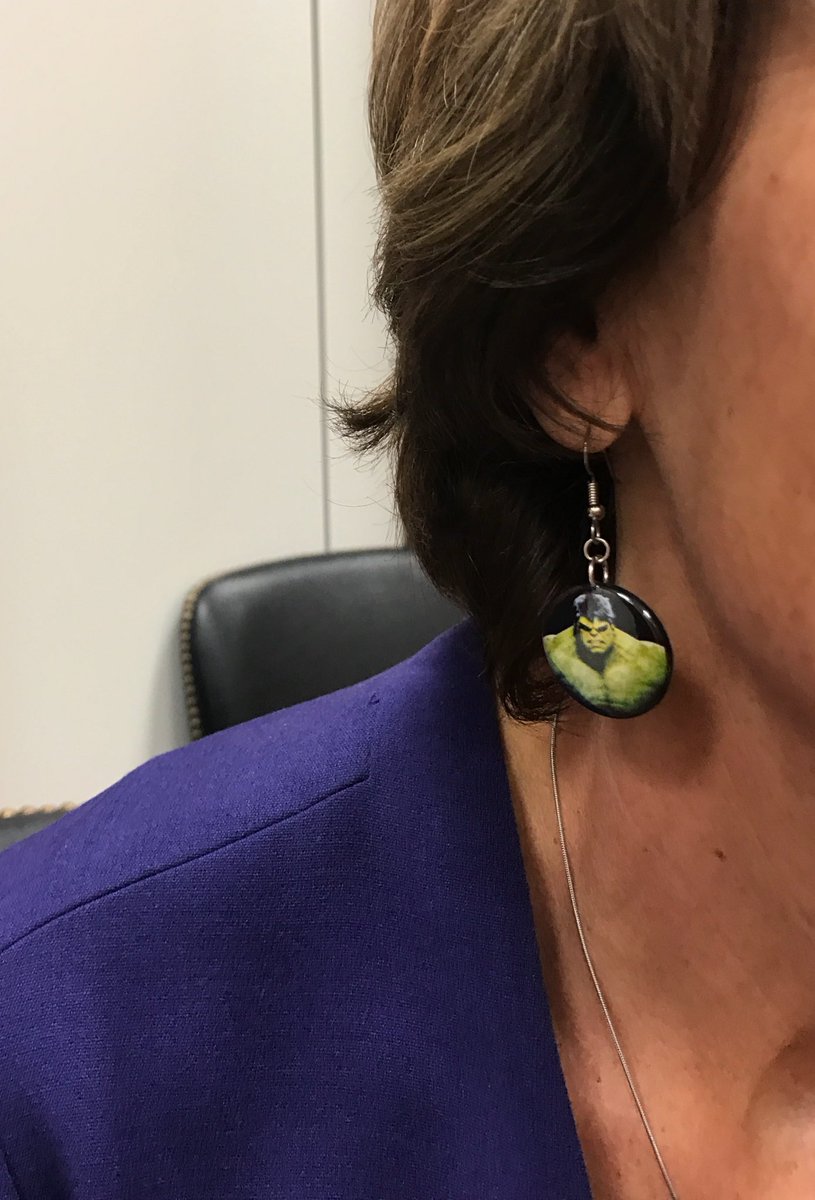

After years of failed attempts, Murkowski, who described herself as superstitious, remained cautious in the final hours leading up to the Senate vote late Tuesday night. She donned earrings depicting the Hulk in honor of Stevens, who was known for wearing superhero ties.

"And when he wore his Hulk tie, he meant business," she told CNN in an interview Tuesday.

She knocked on a wooden table twice while talking about the vote, which was just hours away. "I have learned with ANWR and watching it since truly I was a college student ... you don't take anything for granted," she said. "It's not done until it's done."

Murkowski said she spoke to her father recently about the proposal.

"He was very proud with how we advanced the ANWR bill thus far, although he, too, is superstitious," Murkowski said of her father. "He said 'It's not over until it's over, so we're not even high-fiving, but good luck to you.'"

A heated debate

Critics of the bill were also fighting until the end. Sen. Maria Cantwell, the top Democrat on the Energy Committee, took to the Senate floor to rail against the tax reform bill Tuesday afternoon, blasting Republicans for trying to sneak in the ANWR provision.

"We didn't create the Arctic coastal plain, but I can tell you this -- we cannot re-create it," Cantwell said. "What we're doing today is taking a step towards destroying it."

Protesters -- including some wearing polar bear costumes -- have been canvassing the hallways of Congress for weeks, calling on senators to strip out the provision. Environmental groups have hounded Republicans for using a process known as budget reconciliation to pass the ANWR bill. It's a procedure that allowed the Senate to pass the bill with a simple majority of 51 votes, rather than the usual 60 needed to break a filibuster.

Reconciliation can only be used sparingly, thus it's usually reserved for major legislative efforts. Due to arcane Senate rules, Republicans combined the ANWR bill with their sweeping overhaul of the US tax system and take advantage of the 51-vote threshold opportunity, avoiding the 60-vote pitfall that has taken down ANWR in the past.

"This bill is a disgrace," Gene Karpinski, president of the League of Conservation Voters, said in a statement, arguing that it "would turn one of our last remaining wild places into an industrial oilfield."

Proponents of opening up ANWR argue that environmentalists are overstating the potential impact of drilling in the area. While the heated debate normally takes center stage in Washington around ANWR votes, the emotional clashing was somewhat overshadowed this time in part because it was attached to an arguably more controversial effort.

"I do think that with the tax bill consuming so much of the debate, it has deflected much of what we otherwise might have seen" in terms of pushback, Murkowski said.

Father and daughter -- and 'Uncle Ted'

Frank Murkowski was first elected to the Senate in 1980 and served until 2002, when he ran for governor and won. After reviewing candidates to appoint as his replacement in the Senate, he went with a controversial decision to pick his daughter, Lisa, who was a state legislator at the time.

It was a highly unpopular move and critics cried nepotism. Lisa Murkowski went on to win election to a full term in 2002. She was defeated in the 2010 Republican primary by tea party-backed candidate Joe Miller, but she waged a successful and historic write-in campaign to beat Miller in the general election. Last year, she won re-election to a third full term.

Her father's tenure as governor was marked by other controversies, including his decision to spend $2.7 million on a government jet, despite disapproval from the legislature. He also ended a program that gave longevity checks to senior citizens to encourage them to stay in the state after they retired. "That (program) was extremely popular among older people, and all of those older people tended to vote," said James Muller, a political science professor at the University of Alaska Anchorage. "And they turned hard against him when he advocated and successfully piloted legislation that repealed it."

In 2006, Frank Murkowski finished third in the GOP primary for his re-election bid, and Sarah Palin went on to become Alaska's next governor.

For her part, Lisa Murkowski rose up through the Senate under the mentorship of Stevens, who she lovingly refers to as "Uncle Ted." She now serves alongside Dan Sullivan, the junior senator from Alaska who was also heavily involved in the ANWR fight.

Murkowski has taken heat from conservatives for some of her positions and votes -- including her "no" vote on a bill to

repeal the individual health care mandate this summer -- but she has largely voted in step with the Republican Party.

After Republicans added a similar repeal of the mandate to tax reform, it was unclear whether Murkowski would still support the tax bill. But she argued this mandate repeal was different because previous versions she opposed also had changes to Medicaid, which she opposed.

She not only supported the tax bill, she helped co-manage it. She served as one of the Republican conferees when the House and Senate hashed out their differences in conference this month to finalize the bill.

All in the family

Republican Sen. Chuck Grassley of Iowa, who's worked with both father and daughter in the Senate, described them as "quiet work horses." Being in the Alaska delegation, Grassley argued, can be a lonely job, especially when working on a major legislative task that focuses specifically on one state.

Sen. James Inhofe of Oklahoma described Frank Murkowski as a "determined" person who didn't talk "in a soft voice" like that of his daughter.

"In retrospect, it seems she's really been a more popular, certainly more visible, and more successful senator than her father was," said Muller, the political science professor.

Lisa Murkowski agreed that she and her father differ in style, but she argued they served at very different times in American politics. "I never thought it was fair to compare my legislative style with my dad's because I didn't serve with him," she said. "I just know him as my dad."

The former senator and governor now spends his days weighing in on policy debates in Alaska and advising on state-specific issues.

To underscore the generational aspect of the ANWR debate, Lisa Murkowski recalled the day of the ANWR vote in December 2005. As she was telling her sons at the breakfast table that day about the bill, her youngest son, who was in seventh grade at the time, was puzzled. "I thought grandpa fixed ANWR a long time ago," he said, according to the senator.

"It was just one of those comments where you realize that for Alaskan kids, they've always known that ANWR was one of these things that was out there," she said. She would come home that night to tell her son they once again failed to pass the bill.

Matt, her son, is now 25, and Murkowski said she spoke to him again ahead of this week's vote.

"I was like, 'OK Matt, we're going to get it done,'" she said, knocking on wood again. "This time, Mom's fixing it."